Webinar Summary

The following summary is auto-generated from the webinar recording.

Solar makes many remote IoT deployments viable and cost effective — but only when the power math is right and your connectivity strategy is ruthlessly efficient. The two simple outcomes to shoot for are improved uptime and lower BOM costs. Do those well and you can power devices year round with tiny panels and small batteries. Do those poorly and you end up over-sizing panels and chasing downtime.

Start with a Real Power Budget

Before buying panels or committing to a battery chemistry, figure out how much energy your device actually consumes in the field. A surprisingly small number of minutes spent measuring will save weeks of rework and thousands of dollars in wasted hardware.

Practical measurement flow:

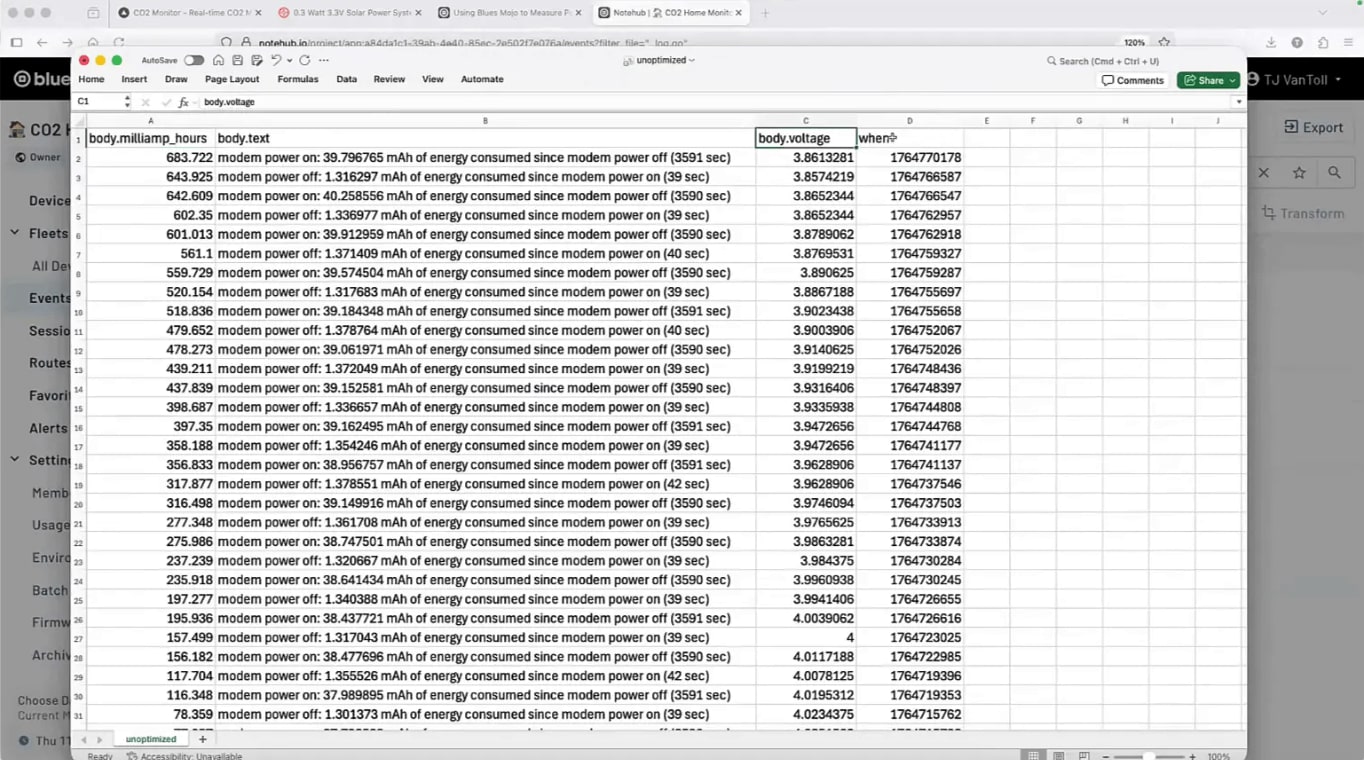

- Instrument the device with a Coulomb counter or power logger like Blues Mojo so you can record milliamp hours over time.

- Run the device in its real configuration — same firmware, same sensors, same radio behavior — and capture multiple days when possible.

- Export the logs to CSV and compute daily milliamp hours and watt hours by multiplying by the device voltage.

For example, a naively implemented CO2 monitor that keeps the host MCU and radio always powered and merely delays between readings consumed roughly 950 mAh per day, which mapped to about 3.5 watt hours daily on a typical LiPo voltage. That baseline is why measurement first matters: it tells you whether a tiny solar panel is realistic or whether you are going to need something much larger.

Tools that Make Measurement and Iteration Fast

Two tools I recommend early on:

- Inline Coulomb counter to measure milliamp hours while the device runs in place or out in the field. This gives a running total you can pull remotely or export for analysis.

- Solar intensity meter to validate how much sun is actually hitting your panel during tests. Point the meter and the panel at the sun and compare watts per meter squared to expected panel output. On a clear day expect ~1000 W/m².

Right-size Solar Panels for the Worst Month

Design for the worst month of the year, not summer. Short winter days, low-hanging clouds and seasonal shading are what determine whether a device will remain online.

Key rules of thumb:

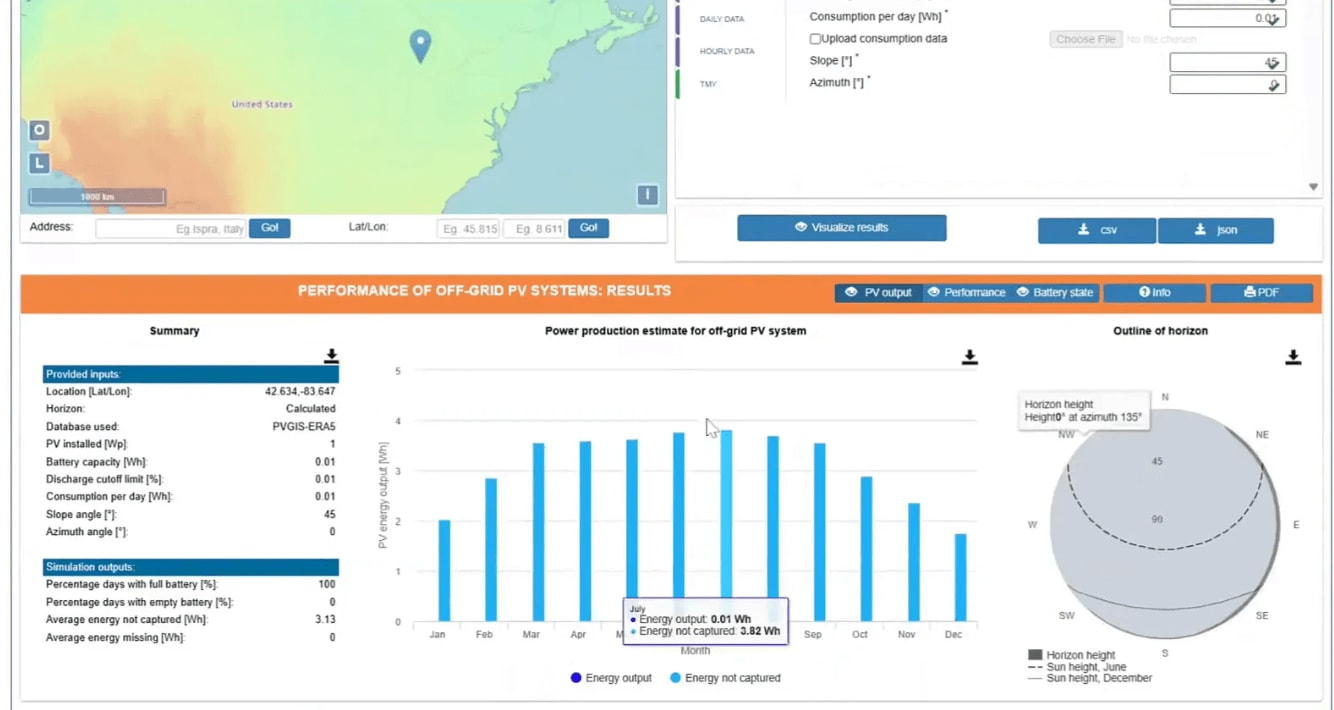

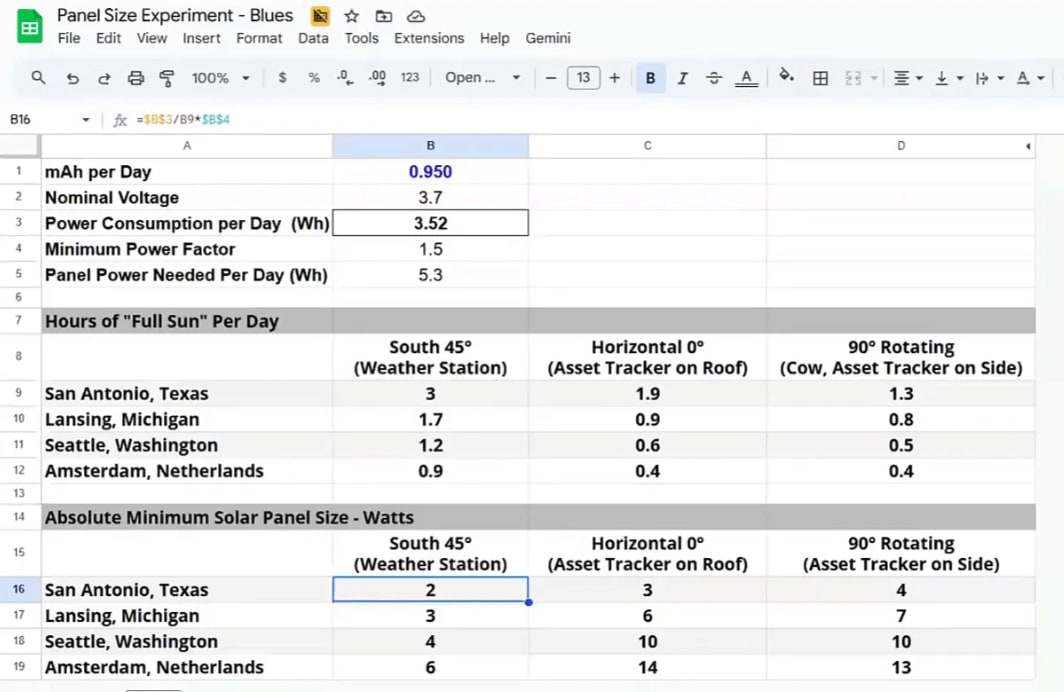

- Use location-based solar data. Tools like PVGIS give realistic average daily equivalent full sun hours for any location and panel orientation.

- Account for orientation and mounting. A south-facing tilted panel will produce far more winter energy than a flat or north-facing surface. If your device rotates or faces random directions (shipping containers, vehicle trackers, cattle tags), expect significantly less effective sun hours.

- Build headroom into your panel sizing. Aim for a panel capable of producing at least 150% of your average daily consumption. That margin increases robustness across multi-day cloudy stretches and seasonal lows.

Example sizing: That unoptimized 3.5 Wh/day device would need a panel capable of >5 Wh/day. Depending on location, that might be a 2 W panel in a sunny winter location, or a 4–10 W panel in cloudier regions.

Pragmatic Site Evaluation

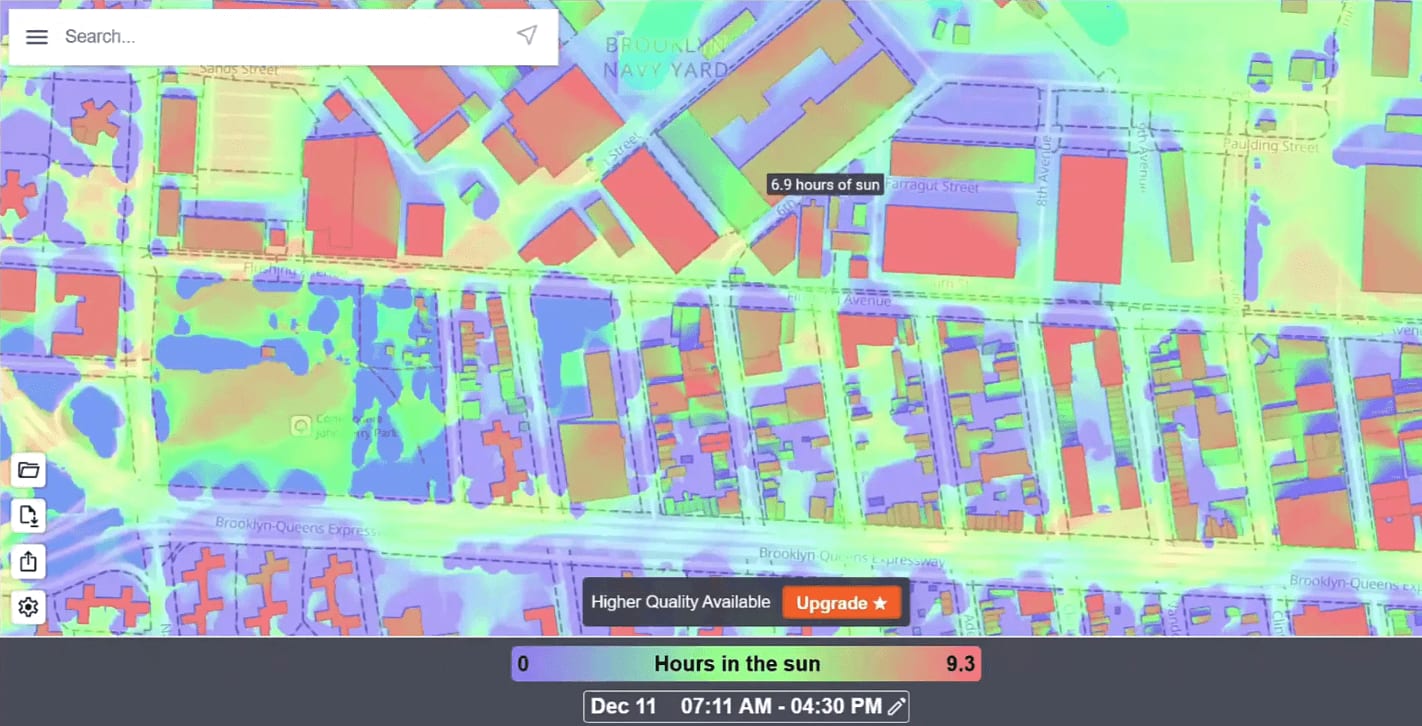

Small changes in placement can swing available energy dramatically. Before mass deployment:

- Use shade mapping to evaluate a location at the time of year you care about. ShadeMap.app and similar tools visualize building and tree shadows throughout the day so you can spot poor locations in advance.

- If you can choose mount points, prioritize unobstructed southern exposure and tilt where possible.

- Measure real-world panel performance with the solar intensity meter plus your chosen charge controller and storage to confirm energy actually reaches the battery efficiently.

Example of using shademap.app to show a heatmap of hours in the sun per location.

Make the Radio Work for You: Notecard Power Strategies

The wireless module is often the largest single drain in a connected product. Follow three guiding ideas for the Notecard or similar connectivity modules:

- Leave the connectivity module powered on. Notecard is designed for low power and idles in the microamp range. Repeatedly powering a modem off and on is usually more expensive in energy than leaving it in a low power idle.

- Batch and store data locally. Flash storage is plentiful on Notecard. Save many sensor readings locally and forward them in a single connection rather than connecting every few minutes.

- Extend the sync cadence. Use

periodicor voltage variable sync modes so the module turns the radio on only when needed. Stretch sync intervals as far as your application can tolerate. Every reduction in connection frequency buys big savings.

Measured example: a continuous connection syncing every five minutes drew

about ~157 mA over 12 hours. Switching to periodic mode and syncing every 30

minutes reduced draw to ~9 mA over the same interval.

Variable Sync Based on Battery Voltage

Make sync cadence adaptive. Configure different outbound/inbound sync intervals aligned to voltage thresholds so the device sends frequently when the battery is healthy and throttles back during low-charge conditions.

Use presets or custom thresholds for LiPo, alkaline, LIC and other chemistries and tell the radio the type of power source so thresholds are meaningful.

Pick the Right Cellular Flavor

Not all Notecards are equal when it comes to power consumption. Midband Notecards can be substantially more efficient than other generations. Profile the Notecard you are considering under real signal conditions and choose the best fit.

Let Notecard Act as Mission Control

Notecard can also control the host MCU power. Wire the ATTN pin from Notecard to the host EN pin and use scheduled or event-based wake triggers to power the host only when it must take readings.

Wake triggers can include:

- Periodic seconds-based wake

- Inbound Notes from Notehub

- Onboard motion detection

- Environment variable changes

Measured Baseline to Optimized Deployment

Applying the above in practice is revealing. A backyard CO2 monitor moved from a naive design that used ~950 mAh/day to an optimized setup that consumed roughly 34 µAh over 52 hours of testing. That converted a 3.5 Wh/day load into roughly 0.1 Wh/day.

What that means in practice:

- A tiny panel and a lithium ion capacitor become viable options across a much wider set of climates and mounting orientations.

- Smaller batteries, lighter enclosures and simpler mounts reduce BOM and installation costs.

- Once power is low enough, solar engineering becomes a predictable mechanical sizing exercise rather than a continual game of triage.

Battery and Environmental Considerations

Battery chemistry and temperature ranges matter. Lithium ion capacitors (LICs) offer wide temperature tolerance and shipping advantages compared with some LiPo formulations. For industrial deployments, aim for enough stored energy to survive the expected worst-case number of dark days. Typical minimum guidance is at least five days of autonomy; some deployments require tens of days.

Solar cell efficiency drops with temperature above roughly 25 °C, but hotter conditions often come with more sun, so the net effect is usually manageable. Battery charge and discharge temperature limits are the more critical design constraint.

Practical Checklist (Before You Ship)

- Measure real device consumption with a Coulomb counter in the field.

- Calculate average daily watt hours and add at least 50 percent margin for panel sizing.

- Use PVGIS or similar tools to get location and orientation specific sun hours for the worst month.

- Validate panel to battery charging efficiency with a solar intensity meter and verify charge controller behavior in low light.

- Choose battery chemistry and capacity to survive the expected number of dark days plus temperature extremes.

- Optimize firmware: batch data, increase sync intervals, disable unused features, and use the radio to control host power.

- Prototype with a note carrier and test deployments in a few realistic locations before scaling.

Final Thoughts

Designing solar into a connected product is not mystical. It is careful measurement, sensible margins, and smart firmware coupled with the right hardware choices. Start by measuring; then reduce power in software. Once consumption is tiny and predictable, the rest is sizing panels and batteries to your climate and placement. That sequence delivers reliable uptime and keeps BOM costs down.

"Produce more power on average than you consume."

Small panels, smart radios, and adaptive firmware let you scale solar-powered IoT from hobby projects to industrial fleets without over-engineering!